Site-blocking legislation won’t fix Australia’s piracy problem

Piracy is a topic that has been on everyone's lips lately. Game of Thrones again demonstrated our convict nation's affection for copyright infringement; per capita, we're the world's biggest offenders. When you consider this, it's no surprise that the government is looking to implement preventative measures such as its proposed site-blocking legislation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to CyberShack as a publication. CyberShack does not endorse piracy.

Piracy is a topic that has been on everyone's lips lately. Game of Thrones again demonstrated our convict nation's affection for copyright infringement; per capita, we're the world's biggest offenders. When you consider this, it's no surprise that the government is looking to implement preventative measures such as its proposed site-blocking legislation.

Unsurprisingly, industry and copyright bodies both think it will be an effective solution, quoting one set of statistics to support their cause; while internet service providers (ISPs) disagree, pointing to a different set of numbers. One group says the legislation will turn people to legitimate sources, whereas the other says Australians will just turn to VPNs to mask their online activities.

There's merit to both arguments, but there's a bigger problem at hand: these groups are arguing over old technology.

Sure, you could strike down torrent repositories such as The Pirate Bay, but this will only cause individuals to find another solution, and it's not necessarily just going to be another website, and it's not necessarily going to be easy to block.

One of these has already emerged: Periscope. It might sound odd, but Periscope – Twitter's live-streaming app – is already becoming a popular solution for piracy. Just this weekend, hundreds of Periscope users streamed the fight between Mayweather and Pacquiao to thousands of viewers each. The quality wasn't amazing, but it saved myriads of potential customers USD$100 each.

Despite this less than stellar quality, Periscope users have also been streaming episodes of Game of Thrones through the app. They're literally putting their iPhone on a tripod, pointing it at their television, and broadcasting the show (and their lounge-room) to the world. This practice has been widespread enough that HBO has already sent Periscope takedown notices.

So how do you police Periscope? If you block users streaming paid-for content, they can simply make a new account. You can't just block an entire app based on the notion that some people might use it to do something illegal. It's possible that Periscope could implement content identification algorithms similar to those used by YouTube if the problem becomes larger, but these would have to be a great deal more advanced to account for the fact the image is being displayed on someone's TV. Until recently, even a mirrored or slightly cropped image would fool the system.

With Periscope's growing popularity, it's easy to see live-streaming becoming a big issue for rights holders: one that site-blocking won't at all be able to fix.

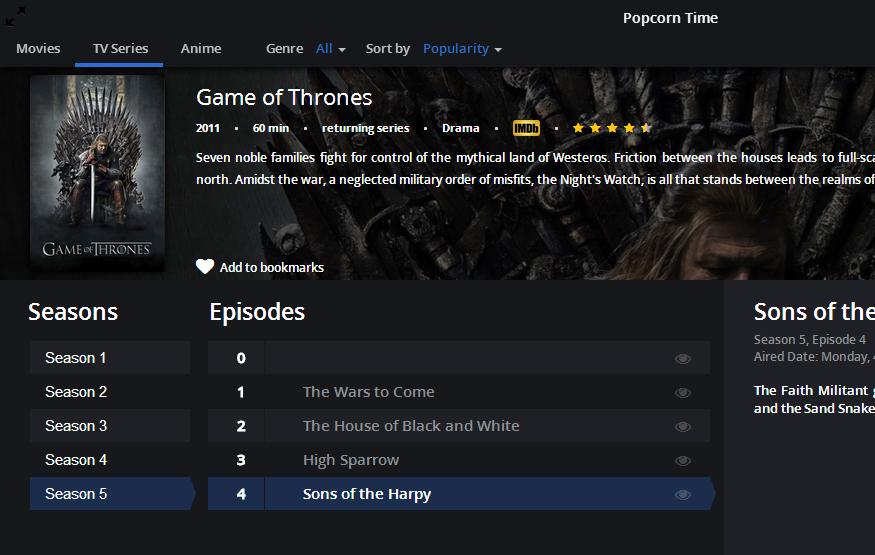

On the other end of the spectrum we've got Popcorn Time, the somewhat infamous "Netflix for pirates". Popcorn Time is a clean, easy to use application that resembles most streaming services on the market. The big difference is all of the content on it is illegal. The shows and movies available on Popcorn Time are also delivered to the user via BitTorrent technology, but through a greatly simplified interface. There's no need to trawl through torrent directories, you simply click on what you want to watch and start watching.

Popcorn Time's illicit nature means you can watch almost anything you want through it. As soon as the new episode of Game of Thrones finishes airing, its available to view on Popcorn Time. The appeal is undeniable.

As such, It's not surprising that the U.K. government has tried to crackdown on the rogue streaming service. Several British ISPs will be required to prevent access to sites that offer the app for download, but that's the equivalent of a putting a Band-Aid on a shotgun wound. The actual Popcorn Time application is only about 20 megabytes, meaning its small enough to share around via cloud storage services such as OneDrive or even email. Theoretically, it would be possible for someone like Microsoft or Dropbox to detect the application and delete it, but putting Popcorn Time in a ZIP or RAR would bypass this.

There is however a silver-lining for rights holders: since Popcorn Time makes use of BitTorrent technology, it's still possible to detect who's downloading and uploading, provided the app's users aren't masking their identity through a VPN. Nonetheless, the fear of getting caught doesn't appear to deter many.

Legislation and lawsuits won't kill piracy; copyright infringement didn't end with Napster or Kazaa, it evolved. And as sites like The Pirate Bay and Kickass Torrents are threatened, new sites will rise up, and so will new technologies. I'm not saying piracy is justified, but forcing Australian ISPs to block torrent repositories won't stop it.

Enterprise theory suggests that organised crime exists because legitimate markets leave customers and potential customers unsatisfied, and while piracy isn't exactly run by the mafia, there's clear parallels. Netflix's chief content officer Ted Sarandos agrees with this, and has said that the reason most people pirate is the lack of cheap legal alternatives.

Of course, you're never going to satisfy everyone, and some people will keep pirating regardless of cheap, legal alternatives; House of Cards is still available on torrent repositories despite being available for a low cost on Netflix. That being said, it receives nowhere near as much traffic as Game of Thrones.

Assuming piracy (for the most part) is a symptom of customer dissatisfaction, brutish policies such as site-blocking are the equivalent of cutting out a cancer without treating it; you may have stopped it temporarily, but it will grow back.